Abandon the Pontoon and Enter the Pool

What I’ve been dreaming, making, learning and teaching. Plus, the best books, short stories and essays that I read in 2025. The title is nonsense; I texted it to myself at 3 am

I dreamt of a suitcase, of packing then unpacking it because I couldn’t take everything with me. Last year, after we moved into the house, I read A Life of Meaning: Rediscovering Your Spiritual Center of Gravity while the boxes still sat upon the living room floor and within the bedroom closet. The book is largely directed at people undergoing mid-life crises, but several concepts resonated, such as that of an “adaptive strategy” for getting by in early adulthood.

What powers or presences stood, perhaps invisibly, at the junctures of my life and caused the train of life to go down one track rather than the others? I underlined on page 11. Are these presences still operational in my life? The final chapter is titled for a central concern of the book, which was also my main impetus for reading it, the almost laughably heady question: What does the psyche want?

* * *

Come autumn (that’s May, here) I began insulating the shed in the back of our house, spending my days off stuffing the underside of the corrugated metal roof with insulation, setting in the new drywall ceiling with Sam’s help (see us standing on either side of the ladder in a small dark dusty room— arrrgh you’re not holding it right! shit, it’s in my eye!).

By July, I was able to go in there in the mornings, when it was still cold out, and write without my fingers going numb.

Write what? In a sentence: a short story that might actually be a novella, an art-theory chapbook (working title: Object Archetypes) and, until recently, an ill-fated personal essay about the connection between story and geography and how hard it was to move to Australia. I hesitate to share more, not because I don’t want to hype anything that won’t pan out, but because, refreshingly, this year learning took precedence, for me, over production. I’m secure in the knowledge that good things take time, and that it’s not worth making anything if the process itself isn’t intrinsically gratifying.

The internet, and maybe our post-modern world in general, places a premium on the performance of craft. Thus the #workinprogress photos I used to share of my art; the sped-up videos of me progressively building a ceramic sculpture. I giggle at the thought of how an equivalent might look of me writing at my desk, my facial expression changing like the weather while I flit back and forth between my notebook and the keyboard, dipping out to grab a snack.

When my professional life was a bit more precarious, it was a useful exercise in self-definition for me to share more of my work in progress, and to cultivate a cohesive visual identity on the, erm, Instagram grid. But the validation I received from likes and follows was, of course, deceiving — it had little correlation to my work’s purchase in the real world. Some time ago, I realized that maybe I had been laboring under false pretenses.

Internalizing Models

All of that is to say that, at present, I’m more interested in sharing what I’ve been reading and learning than what I haven’t yet brought to fruition.

Looking back on my progress in writing this year, it was a lot about “internalizing models” in the words of author Samuel Delaney. In the book About Writing, Delaney talks about absorbing the formal frameworks and habits of great writing and writers, “at the bodily level.” As a teacher, I’m super interested in how learning happens, so I thought I’d break this concept down a bit.

What does this mean, “internalizing models”? I see it this way: these days, I feel confident writing an academic essay (at least a short one) because I’ve done it so many times before, and I’ve read so many academic and reported essays, that its defining structural and tonal qualities have pervaded my perceptions, my research practices and my writerly habits. I don’t have to think about how to write so much as what to write, because I understand, at a bodily level, how to attach the form to the content.

Soon after submitting my first fiction excerpts for feedback in February, it became clear to me that I didn’t have an innate sense of the form or scope of a short story. I got caught up in descriptions of people and rooms, and people moving through rooms, that didn’t propel the narrative forward. Through alternately receiving feedback, giving feedback to others, and reading from a writer’s perspective, I became more conscious of the form, but also, I suspect, more unconscious of it. Later in the year, I could sense, without really being able to pinpoint why, that I was making better decisions about pacing, description and characterization. It became more natural for me to sketch out narratives that were not novelesque in scope.

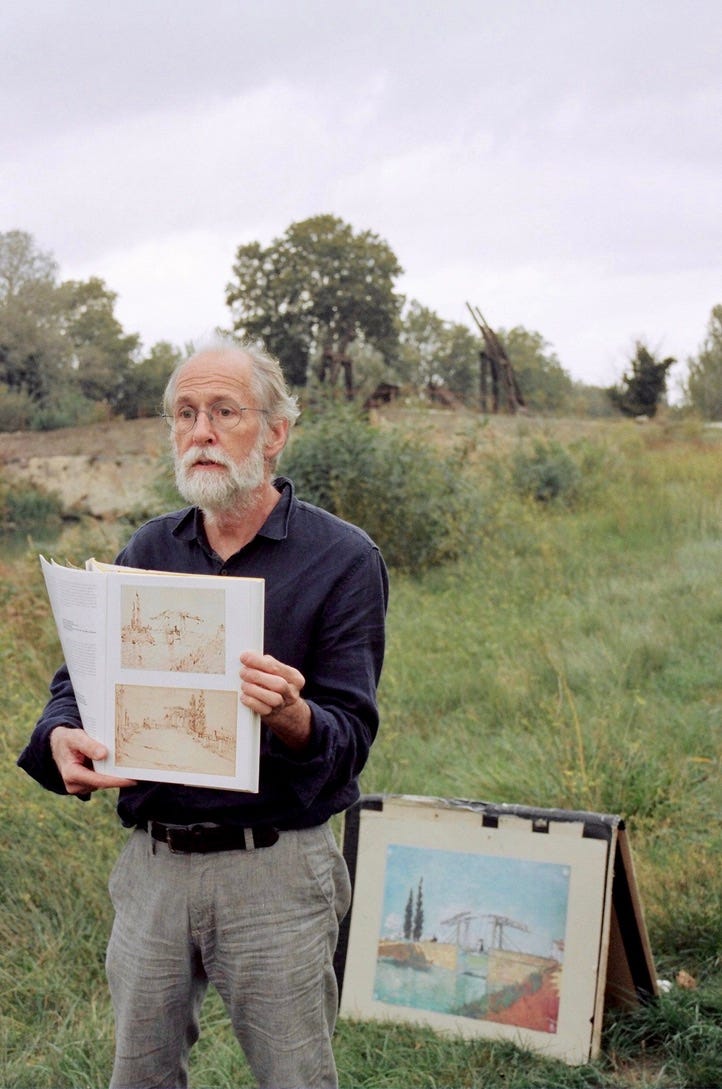

I think back to when I studied painting, at the Leo Marchutz School. We “internalized models” for our craft by collectively looking at and discussing great paintings, but also by copying them. Copywork a way of training our brains and bodies to interpret visual data into coherent, alive, significant images. It was an opportunity for our creative imaginations to enter into a sort of physical dialogue with the mind of a Great Artist.

Copying writing doesn’t quite work the same way, but I have found it helpful to study author’s work from a writerly perspective (with the help of more seasoned writers and workshop hosts), considering how and why the writer chose to share information in one way rather than another, according to their particular vision of the world.

One of the pleasures and privileges of teaching an art-history-essay-writing course for young artists this year was helping them find those models — in art and theory — for themselves. Same goes for the classes I taught in sculpture and ceramics.

The best things I read this year

With that, I’d like to share some of my favorite books, essays and stories I read in 2025. I saw some art, too, but in the interest of not making this Substack as long as my “story_EXTRAS” word document, I’ll stick with the written word this time around.

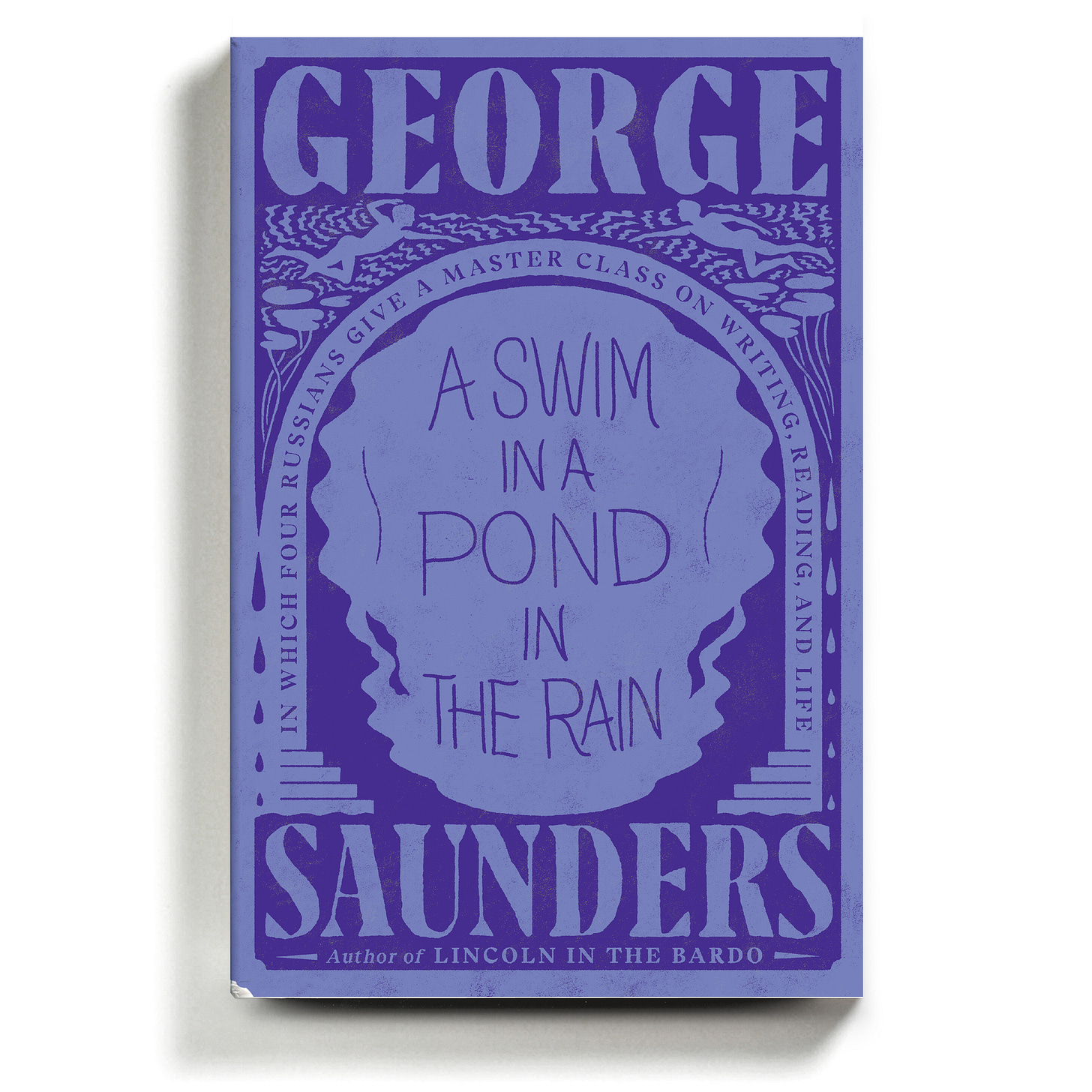

Apropos of “internalizing models,” one of my absolute favorites this year was A Swim in a Pond in the Rain by George Saunders. In the book, Saunders, a prolific short story writer and generous educator, shares seven nineteenth-century Russian short stories before casually, brilliantly reflecting on some aspect of the writer’s craft. Chapter headings include “The Pattern Story” and “The Door to Truth Might Be Strangeness.” My favorite story in the collection was the one for which the book is named, Gooseberries, by Anton Chekhov.

Central to the story is the issue of happiness, as compared to goodness, in light of all the injustices of the world. As the main character Ivan urges his bourgeois companions, one evening: “live not for happiness but for something greater. Do not cease to do good!”

And yet before Ivan’s impassioned monologue, we see him completely abandon himself to joy, as in the following passage:

"Ivan Ivanovitch went outside, plunged into the water with a loud splash, and swam in the rain, flinging his arms out wide. He stirred the water into waves which set the white lilies bobbing up and down; he swam to the very middle of the millpond and dived, and came up a minute later in another place, and swam on, and kept on diving, trying to touch the bottom.

"Oh, my goodness!" he repeated continually, enjoying himself thoroughly. "Oh, my goodness!" He swam to the mill, talked to the peasants there, then returned and lay on his back in the middle of the pond, turning his face to the rain.

Burkin and Alehin were dressed and ready to go, but he still went on swimming and diving. "Oh, my goodness! . . ." he said. Oh, Lord, have mercy on me! . . ."

"That's enough!" Burkin shouted to him."

As Saunders observes, “Gooseberries” does not come out squarely for or against happiness, but complicates the question, as stories tend to do. This is something I love and cherish about fiction, and more generally, art — the way it locates ideological tensions in an irreducible tangle of experience.

Completely by chance, I finished the story, and the book, the day that Sam and I arrived at an AirBnB in the countryside to meet friends…along a sort of pond. It rained a bit, and, yes, we swam. For a time, we forgot the horrors of the world.

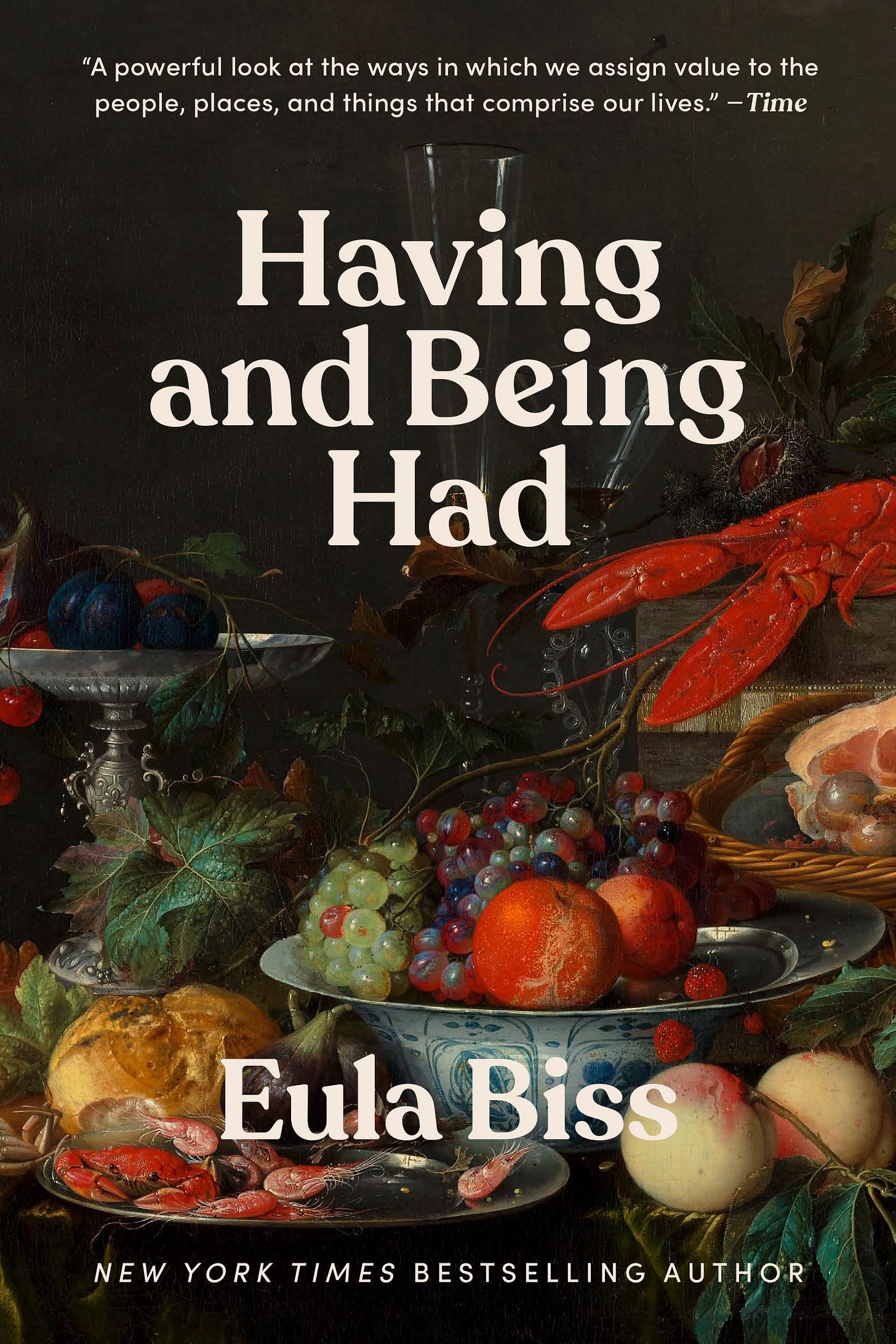

Two other standouts were each meditations on domestic life, and homeownership — what it means to settle down in a new house or a new country. Things I can relate to. These books were Having and Being Had by Eula Biss and The Anthropologists by Ayşegül Savaş.

I actually read Having and Being Had at the very end of 2024, before passing it off to Sam, and then my dad, who were with me, along with my mom and sister, on a hiking trip through the Saint Charlotte’s track at the top of New Zealand’s South Island. It was the subject of many good conversations as we walked.

In the book, Biss eloquently grapples with her participation in capitalism as a new homeowner, writer and professor. She considers the nature of work, leisure, possession and consumption as she shops for furniture, speaks to her husband and to friends, works in her office, looks at art, etc. These ideas, grounded in her lived experiences, are contained in short chapters which consider and complicate the concepts for which they’re named — like “Art,” “Work,” or “The Protestant Ethic.”

Interestingly, The Anthropologists by Ayşegül Savaş is also structured in short chapters with categorical headings. The book sees the protagonist and her partner looking to purchase an apartment in an unnamed European city in which both live but neither are from. While apartment-hunting, the protagonist, a filmmaker, sets about interviewing people in the local park. These strangers’ reflections on their rituals in the park are juxtaposed against the narrator’s own meditations on the rituals, objects, and people that define her life in the city (being that she lacks a single culture to which to attach herself).

I first encountered Savaş about a year ago, when she read and discussed a short story called “The Abduction” by Tessa Hadley for the New Yorker Fiction podcast. I loved that story, and subsequently sought out the work of both Hadley and Savaş, whose short stories I’ve also enjoyed.

One more book I read this year that I’d recommend was When We Cease to Understand the World by Benjamin Labutut. It’s a hybrid work of non-fiction and fiction about 20th century physicists — including the man who invented a chemical responsible for both a revolution in agriculture (life) and mass killings in World War II (death). Fascinating, terrifying stuff.

Essays & Stories that I read and loved

i. Favorite Essays (many of them pretty devastating, but not without humor):

Reframing Vermeer by Teju Cole (2024), Pirates of the Ahuyasca by Sarah Miller, (2025), Repeat After Me by David Sedaris (2007) Introduction to Revolution in the Head by Ian MacDonald (1994) The Arrow and the Wound: The Art of Almost Dying by Mark Slouka (2003), The Sloth by Jill Christman (2008) The Reenchanted World by Karl Ove Knausgaard (2025)

Somehow I managed to acquire an English degree without reading this: Politics and the English Language by George Orwell (1946)

ii. Favorite Stories (most from the New Yorker):

A Fabulous Animal by Samanta Schwebelin (2025), An Abduction by Tessa Hadley (2012), Signal by John Lanchester (2017), The Chartreuse by Mona Awad (2025) P’s parties by Jhumpa Lahiri (2023), Safari by Jennifer Egan (2010), The Magic Bangle by Shastri Akella (2023) Travesty by Lillian Fishman (2025)

Many of these stories I listened to via podcasts on commutes to work. Others I read in magazines, anthologies, books or via George Saunders’s Substack, Story Club.

Some of them can be found in my study, stacked alongside print-outs of my own writings-in-progress, my cheap composition notebooks of longhand drafts. At year’s end, the room has the gentle mess of a person at work.

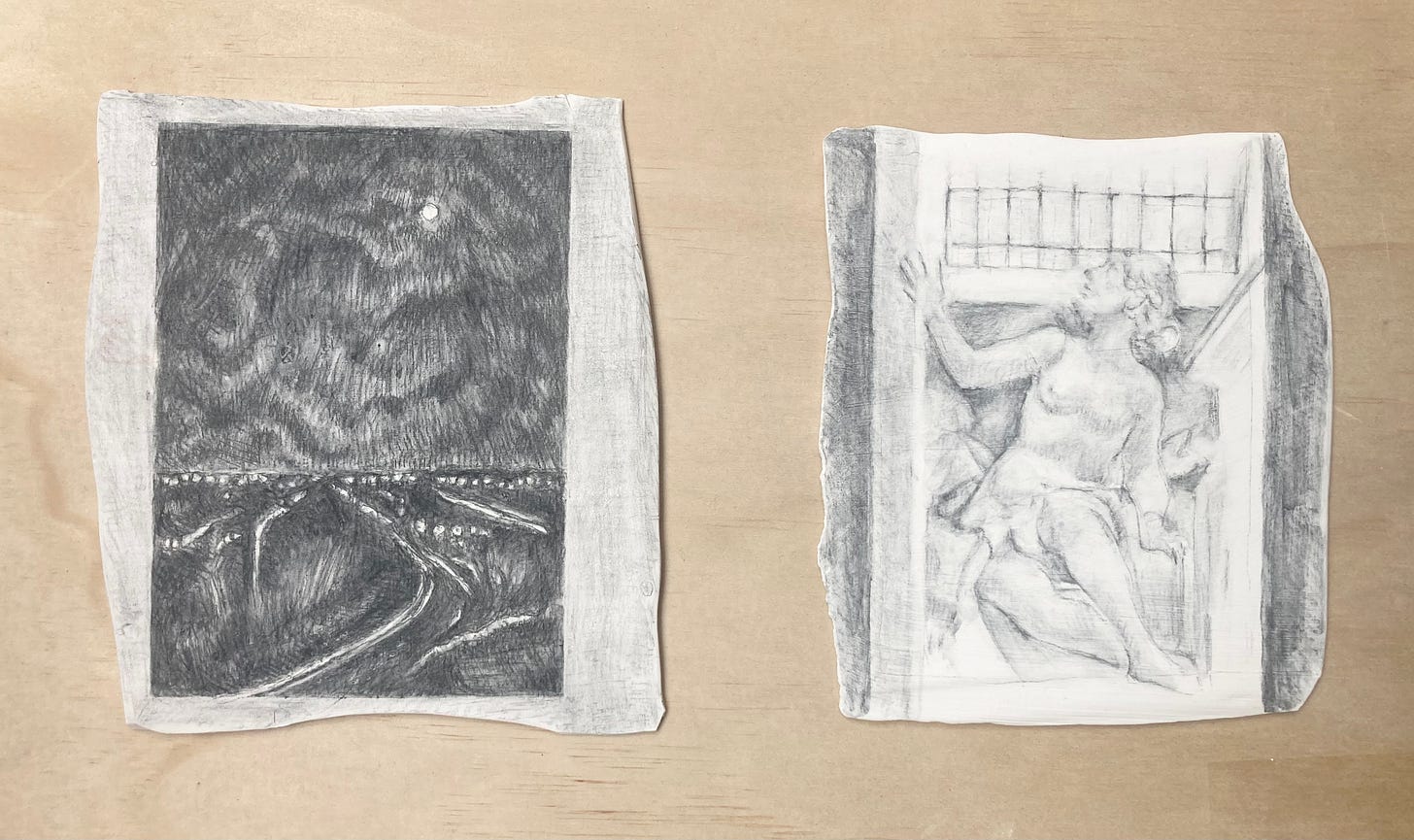

If you were to step into my study, you would also see drawings, on the countertop/bench above the washing machine (half of the study is a laundry). Slowly and sporadically, I’ve begun to transfer and enlarge images from my vast, beloved archive of sketches into finer drawings on slabs of porcelain, that finest of materials. Currently, the drawings are only bisque fired — when fired at a higher temperature (Cone 6), the image will be baked into the material.

These, too, are packed in my proverbial suitcase.

I hope you find some joy this holiday season. If it’s in short supply, allow me to make two final recommendations: One: this beautiful hand-painted animation by Alison Shulnik. And two: The music of Duo Ruut, who produced one of my favorite albums of the year. See this video of them singing an Estonian folk song on a hammer-dulcimer by the shore.

Take care,

Kate